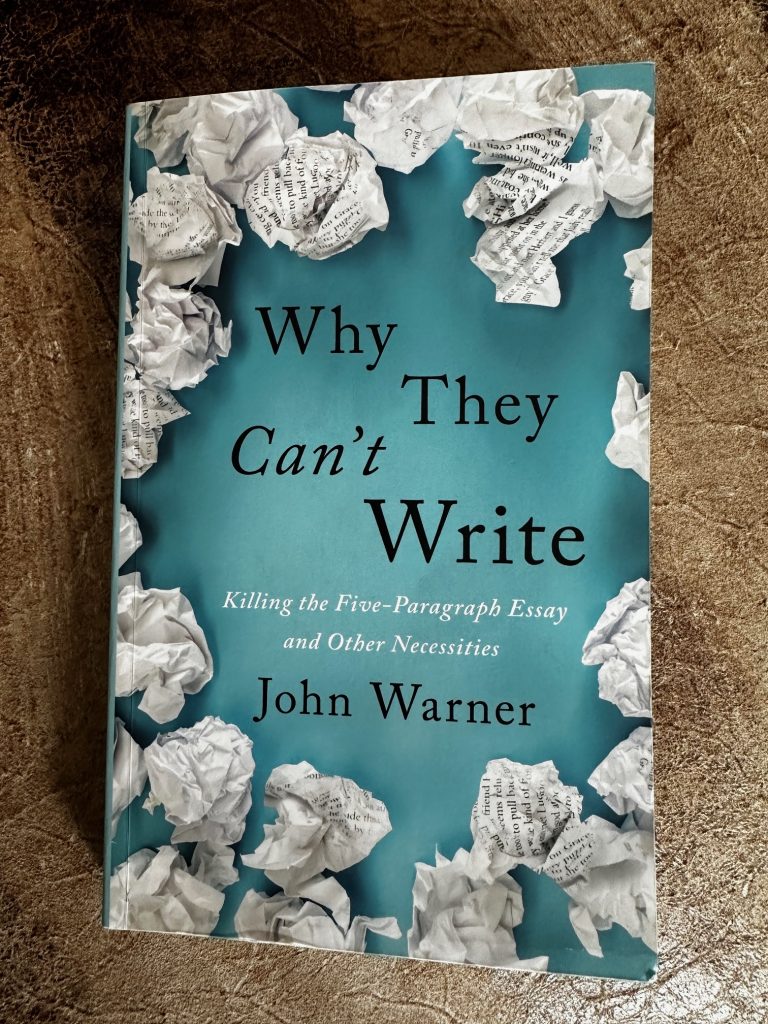

Wow that’s a loaded title! And here the subtitle: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities.

Wow that’s a loaded title! And here the subtitle: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities.

It’s obvious why I wanted to read this book – I’m a writer who has tutored and taught high school seniors and college students for over a decade. While I haven’t “seen it all,” I have seen a lot in terms of what kids that age are capable of when given the type of direction that makes them want to learn. Although I’ve witnessed how far students can come from the beginning of the semester to the end, I’ve also seen how school systems fail teachers, tutors, TAs, and students. It sucks. So when I came across John Warner’s book about why students and adults can’t write, I wanted to know his take. Page one of chapter one, which is called “Writing Crisis,” asks two questions: Why can’t my new employees write? (not funny) and “Why do they keep saying “plethora”? (I laughed out loud at this one).

Over the course of the book, Warner explains why the five-paragraph essay is antiquated, why students love learning but hate school, the role of research papers, and how the school system prioritizes testing over learning to write well. All true. The author says, “Even at its inception, the five-paragraph essay was a tool of convenience and standardization.” He also points out that “our incentives align against teaching students to write (and think), and instead favor a performance of proficiency.”

My friend’s 11-year-old son, who is an excellent writer for his age, is getting penalized at school because he is not writing “quick enough.” His grades in English class are suffering because, as a fifth grader, he’s being asked to write a five paragraph essay in 45 minutes (which is ridiculous) rather than being praised for his ability to write well and think critically. As both a professional writer and a parent, this type of standardized bullshit blows my mind. It also makes me anxious because in a few years I’ll most likely be dealing with this nonsense with Fleet. Warner blatantly states, “We are training students to pass standardized assessments, not teaching them how to write.” Exactly. But what do we do about it?

Throughout the book, the author provides thoughtful ideas, concepts, and strategies that schools “should” implement – i.e.“resources, time, and motivation” – but he also knows that a lot of his suggestions are a long shot. For example, teachers “should” be paid more. Of course that’s true, but where is the cash going to come from? He’s smart enough to admit that he doesn’t know. That being said, the author has done his research and provides ample support that backs up his claims. Here are a few that caught my eye:

“Only a ‘rare few’ find writing ‘easy.’”

“Being human isn’t a sign of catastrophic defect.”

“Writing is a public and even collaborative act.”

“Part of the writer’s practice is to be…open to surprise or revision.”

“Young people know lots of things, but they often know little about the things they are asked to write about in school.”

“It is very rare to see a five-paragraph essay in the wild; one finds them only in the captivity of the classroom.” (I laughed out loud at this one too).

“Two of the most important traits for students to develop to succeed at education in general, and writing in particular, are agency and resilience.”

“Writing is a skill, but it is a skill that lives inside the person that often develops through idiosyncratic and individually driven processes.”

“Students find writing meaningful when they understand how the writing fits inside the larger picture of their lives and experiences.” (Yes! There is no “when will I ever use writing as an adult” question because they know they will).

“One of the skills students should be developing is the ability to make observations and draw inferences from those observations. This is a core element of critical thinking – the ability to look at the world and make interesting and valid conclusions from what we see.”

“Learning to write is a process, not a product.”

While Warner provides a plethora (ha!) of gems, one of the most important is his explanation of the subjectivity of writing. He says, “The belief that response to writing can or should be standardized is, and I say this with all due respect, silly.” He is absolutely correct and I wish others would acknowledge, learn, and teach this because it’s imperative to understand that writing does not come with a formula or an equation. End of story. Turning writing into a test takes away the essence of why writing matters and shows how people have “spent a lot of time examining trees without being required to describe the forest.” Additionally, the author tells his students that “writing will make them capable of experiencing empathy for others while also acting with personal agency inside a complex and contradictory world.” He’s right and, since I assume he’s a good professor, I bet his students remember those words of wisdom.

As I said earlier, Warner did his research and clearly consulted a long list of sources for this book. One of the most significant citations is from Susan Engel who “argues for the necessity of putting children’s natural curiosity at the center of the classroom.” Fleet will start kindergarten in the fall and there are many elements of uncertainty, excitement, and anxiety that go along with such a big milestone. I can only hope that wherever he ends up, his teachers know that although they have a job to do (and aren’t necessarily in total control of how they are “allowed to” do their job), their primary responsibility is to help students become lifelong learners, not check boxes on a scorecard.

Leave a Reply