Everyone knows Shel Silverstein. His books The Giving Tree, Where The Sidewalk Ends, and The Missing Piece – just to name three – are considered children’s classics. In fact, his books have been translated into more than 30 languages and have sold more than 20 million copies. He also won two Grammys and a Golden Globe, and was nominated for two Oscars. He wrote Johnny Cash’s “A Boy Named Sue” and Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show’s “Cover of the Rolling Stone,” as well as songs for Kris Kristofferson, John Prine, Emmylou Harris, Waylon Jennings, and Loretta Lynn, among others. Additionally, Silverstein was posthumously inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2002 and into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame in 2014.

Everyone knows Shel Silverstein. His books The Giving Tree, Where The Sidewalk Ends, and The Missing Piece – just to name three – are considered children’s classics. In fact, his books have been translated into more than 30 languages and have sold more than 20 million copies. He also won two Grammys and a Golden Globe, and was nominated for two Oscars. He wrote Johnny Cash’s “A Boy Named Sue” and Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show’s “Cover of the Rolling Stone,” as well as songs for Kris Kristofferson, John Prine, Emmylou Harris, Waylon Jennings, and Loretta Lynn, among others. Additionally, Silverstein was posthumously inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2002 and into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame in 2014.

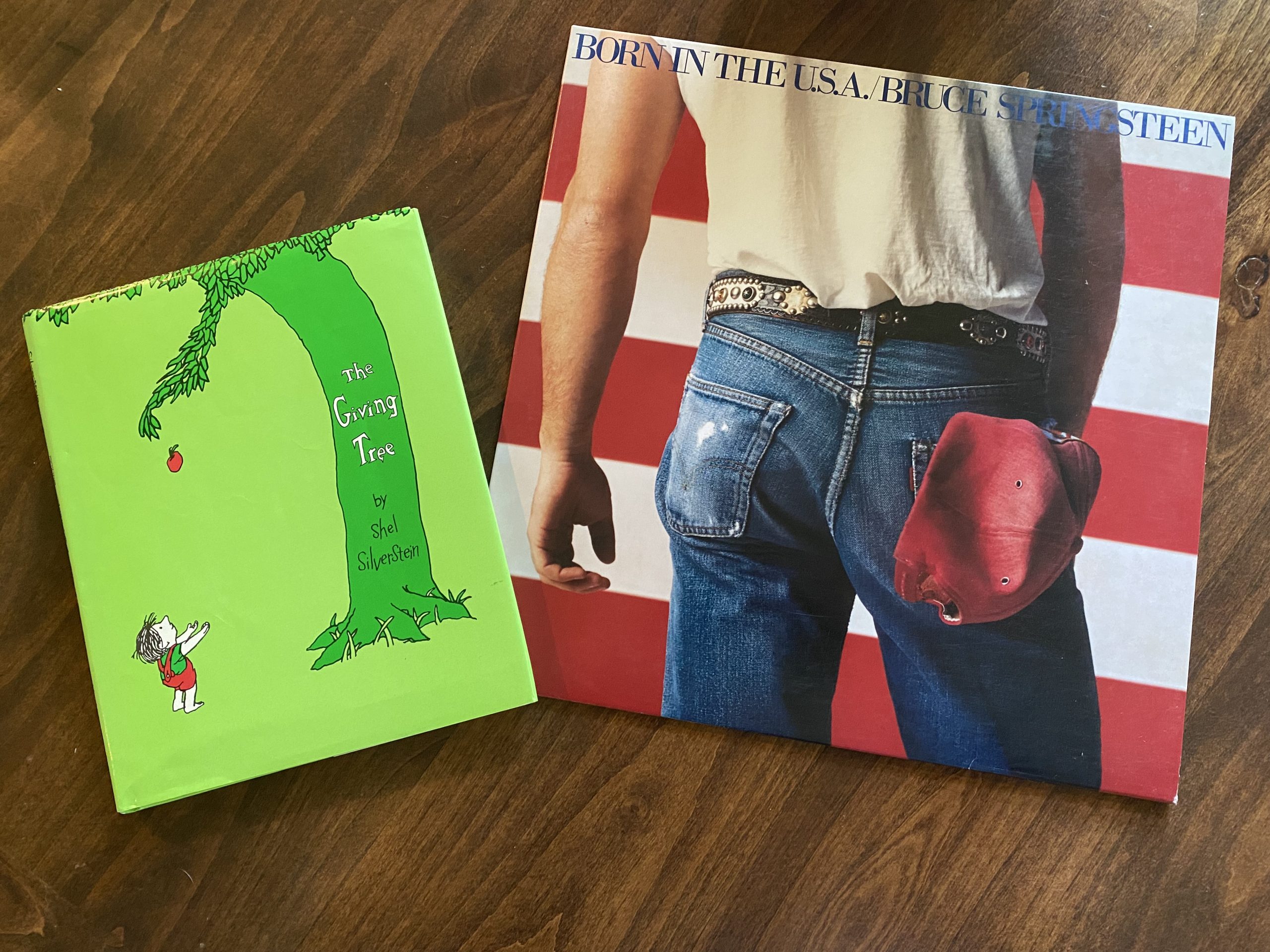

Clearly Silverstein is accomplished and well-known for his writing and drawings, but I can’t get past The Giving Tree’s awful message. At first glance, the story is about a wonderful tree that gives and gives to the little boy she loves but then, upon further investigation (i.e. reading it a bunch of times as an adult), I realized the book actually shines a light on selfishness. The tree gives and gives and the boy takes and takes and, in the end, no one is really happy. Although it may be masked as a book about generosity, that’s not the lesson. Instead, The Giving Tree is similar to Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” in that, at first listen, people think it’s a song that celebrates being a patriotic American when it’s really about how soldiers returning from Vietnam were severely mistreated. “You end up like a dog that’s been beat too much/’Til you spend half your life just coverin’ up/Born in the USA/I was born in the USA.”

So why does this book rank so high on many “best children’s books” lists? TIME’s top ten include Where The Wild Things Are (#1), Goodnight Moon (#3), Blueberries For Sal (#4), and two Silverstein books: The Giving Tree at #7 and Where the Sidewalk Ends at #10. Why didn’t The Very Hungry Caterpillar and Corduroy make TIME’s top ten? And that made me wonder what exactly makes a children’s book great? What sets certain stories apart from others? I think the brilliance of Goodnight Moon is in the prose and rhythm of the words while Hungry Caterpillar is all about the drawings and innovative design with the holes on the pages. Corduroy’s message is the best – that sweet little girl saving her money so she could return to the department store and pick out her very own bear and then fixing the strap on his overalls always makes me smile.

But don’t get me wrong about Silverstein – there is a lot about his writing style that I appreciate. “Cover of the Rolling Stone” is a hilarious satire on the rock and roll lifestyle and his word placement in The Giving Tree is interesting. In the first part of the book (when things are seemingly fun and whimsical) the author breaks up the sentences so that you’re flipping pages quickly because there are only a few words on each page. Then the boy starts growing up and all of the sudden he rarely visits the tree – unless he needs something – and the pages get stacked with words that are mostly comprised of dialogue between the tree and the boy about what he needs and what she is going to give him.

In 2014, in recognition of the book’s 50th anniversary, The New Yorker published an article called ‘“The Giving Tree” At 50: Sadder Than I Remembered.” Writer Ruth Margalit analyzes the toxic relationship between the boy and the tree: “the tree is ‘happy’ to give him her apples to sell. She is likewise ‘happy’ to give him her branches, and later her trunk, until there is nothing left of her but an old stump, which the old man, or boy, proceeds to sit on.” At the end of her article, Margalit makes a fascinating point, that I experienced as well, about reading the book as an adult. Upon realizing that one of her favorite childhood books wasn’t what she remembered, it suddenly “carried with it a peculiar thrill, a kind of scientific proof that [she had] grown up and changed.”

I remember loving the book as a kid and now, of course, Fleet loves it too. When he gets older I’ll explain that any relationship – whether it’s between significant others, friends, colleagues, or a parent and child – will fail if one person is always giving and the other is always taking. It’s not sustainable, it sucks, and it’s sad. The line that is crucial to the story, which I now think is actually more of a satire than a children’s book, is: “And the tree was happy…but not really.” Instead of ending the book right there, Silverstein continues for a few more pages and concludes with the boy (who has become an old man) sitting on the stump with the accompanying line: “And the tree was happy.” By doing so, the author leaves the door open for interpretation while still providing a commentary on selfishness– even if it’s in a children’s book.

Now I want to read it again as an adult.

If you do let me know what you think!