Some stories, no matter how tragic, need to be told. As a journalist, I understand the responsibility that goes with telling someone’s story in the most respectful, truthful, and interesting way possible. It can be rough but also cathartic for the people who are involved, or in Madison Holleran’s case, those left behind.

Some stories, no matter how tragic, need to be told. As a journalist, I understand the responsibility that goes with telling someone’s story in the most respectful, truthful, and interesting way possible. It can be rough but also cathartic for the people who are involved, or in Madison Holleran’s case, those left behind.

In 2015, ESPN The Magazine published an article called “Split Image” which was written by Kate Fagan. Last year I read that article and it was as tragic as it was captivating. It told the story of Holleran, a 19-year-old University of Pennsylvania track runner, who took her own life by jumping off a building – horrifying information that is learned by the reader on the very first page. The reader also learns that the pressures of being a collegiate athlete were part of the problem and that social media – specifically Instagram – painted a much different picture of Holleran’s life than what was really going on with her.

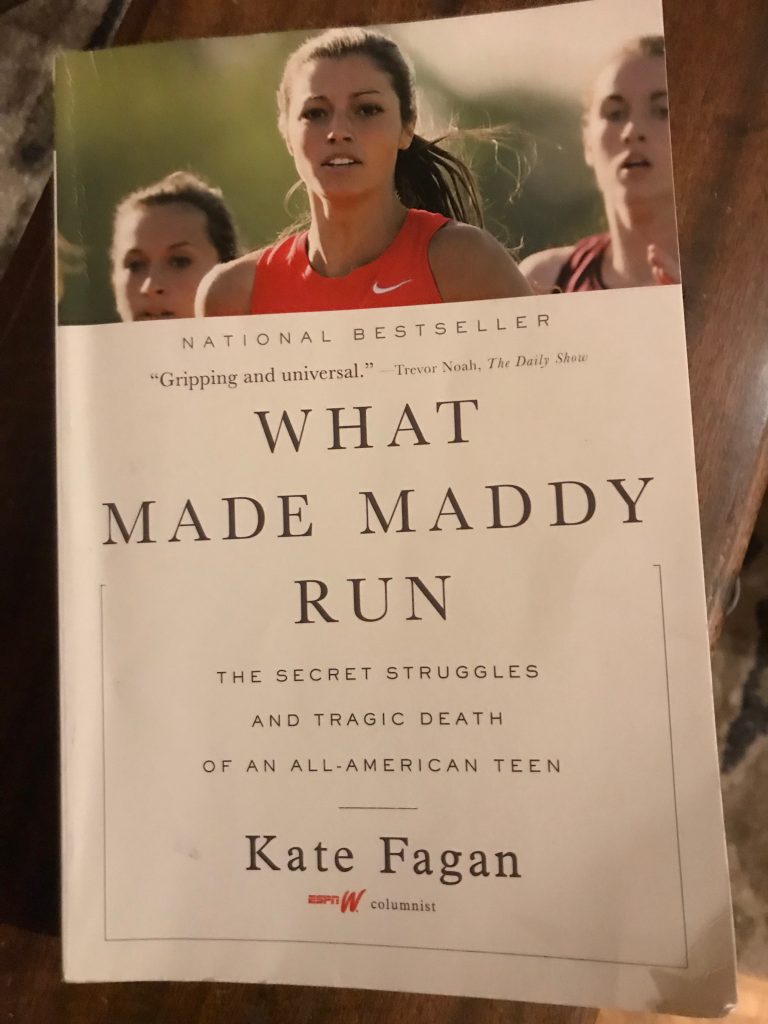

After reading the article last year, I remember thinking that the story would make an interesting book. I was then quickly told that Fagan, like Jon Krakauer with his original Outside Magazine article that became Into The Wild, turned “Split Image” into a book called What Made Maddy Run. While social media clearly wasn’t invented when Krakauer’s “Death of an Innocent” was published, I assume that people were just as shocked by Chris McCandless’s death as they were by Holleran’s death. Consequently, over the years, there has been much debate about whether or not McCandless’s wilderness adventure was a suicide mission (I don’t think it was) but there is no question about Holleran. She left a note. And gifts for her family. And took a running leap off a building because she saw no other way out. It is horrifying.

In the forward, written by ESPN The Magazine and espnW Editor in Chief Alison Overholt, the following statement hits home: “Great narrative journalism has long been about helping us to understand universal truths of the world by grounding big ideas in the stories of real people. I believe that the way we tell these stories can very literally change the way we experience the world.” No truer words.

There is much to be discussed about this book – especially since I took a ton of notes because we are teaching it to our students – but here are a few of my most significant takeaways:

- Fagan is an excellent storyteller. In the Author’s Note, she acknowledges that she “alternately refers to Madison by both her full name and as Maddy” but also points out that there is no reason why she does it. Her transparency, although a minor detail, is much appreciated.

- She has the ability to be descriptive but not so over the top that she loses the reader.

- The author was a collegiate athlete as well – in fact she played basketball for my alma mater, the University of Colorado, and experienced mental health issues while she was there. Her issues weren’t to the extent of Holleran’s but she gets it.

- Copies of emails and text message conversations between Holleran and her friends, family, and teammates are scattered throughout the book which I found interesting. I assume Fagan wanted to ensure that Holleran’s voice was “heard” but also wanted to highlight how much conversation takes place via email, texting, and social media.

- While Fagan spends a lot of time talking about the negative effects of social media, specifically Instagram (Facebook is barely mentioned), she also incorporates information learned from writers and mental health advocates she met via social media – mostly Twitter. She even includes text conversations she had with these people.

- Like a quality journalist should, Fagan seamlessly integrates her research information while telling a compelling story.

- In chapter three, Fagan discusses the importance of having a psychologist as part of any college team’s staff. Because a close friend of mine is a Sport and Performance Psychology professor, I took special interest in this section because so much of what Fagan said relates to what I learned when I audited a couple of my friend’s classes for an article I was writing for the newspaper I worked for at the time. “The importance of a psychologist is this: she may be the only staff member whose job is not related to winning.”

- Penn and Instagram take a serious beating throughout this book – I wonder how both entities feel about it.

- Fagan on Holleran: “She sent thousands of messages, perhaps ten thousand words – and yet little was actually said.” Once again Fagan demonstrates that more communication does not necessarily mean adequate communication.

- Holleran repeatedly acknowledges that she knew something was wrong but didn’t understand why. This quote hit home the most: “It’s hard, not having answers…I just want to know what’s happening to me.” Fair enough.

Interesting terms defined in the book:

- Mental Illness – “everyone struggles with their mental health to a degree because life is hard but mental illness is when that struggle inhibits you from your daily life.”

- Social Media – “an interweaving of public and private personas, a blending and splintering of identities unlike anything other generations have experienced.”

- Digital Native – kids who have grown up on Instagram and Snapchat (i.e. our students) and know no other reality that absorbing hundreds of images each day.

- Emojis – “the world’s first digital universal language… [but] ironically, emojis are devoid of real emotion.”

A few facts learned through Fagan’s research:

- “According to the NCAA, suicide ranks as the third most frequent cause of death among student-athletes – behind accidents and cardiac failure.”

- “One study found that an average high school student today likely deals with as much anxiety as did a psychiatric patient in the 1950s.”

- Although Penn improved its counseling system since Holleran’s death, their efforts weren’t sufficient as six more students took their lives between 2014 and 2017.

- As I read chapter four, I wondered why mental health had become such a prominent issue. I thought I would have to look it up but Fagan had done her research. According to several academic journals, kids no longer get to experience “free play” which is what children used to do when they grew up in their respective neighborhoods riding bikes, going to parks, and playing various games with other neighborhood kids which is the way I grew up. Apparently the absence of free play has contributed to anxiety and various other mental health issues which is extremely unnerving.

Clearly social media plays an enormous role in Holleran’s story – especially the issue of people literally and figuratively filtering their lives via photos. One of the most significant social media issues to keep in mind is reality versus imagery but at the same time I strongly feel that social media is not a place for dirty laundry. In short, it’s a double-edged sword. Fagan provides plenty of commentary on the subject but many of her sources were found on social media which led (I assume) to lucrative speaking engagements at various colleges she discusses in the book. She also lists both her Instagram and Twitter handles on the back cover – but there is no mention of Facebook.

That being said I feel that Fagan is very transparent: “Sometimes it feels much easier to live in that reality than in the one where I am always flawed and challenged, and occasionally sad.” But again, What Made Maddy Run is as much a commentary on mental health as it is a commentary on social media. The author adds, “One of the trickiest parts of social media is recognizing that everyone is doing the same thing you’re doing: presenting their best self. Everyone is now a brand, and all of digital life is a fashion magazine.”

As a PR professional, the idea of everyone being a brand is both interesting and alarming. On page 142, Fagan mentions that positive reactions from social media is like getting a hit of dopamine which reminds me of Jaron Lanier (author of the other book we’re teaching this semester called 10 Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts…) quoting Sean Parker – the first president of Facebook: “We need to sort of give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while, because someone liked or commented on a photo or post of whatever…you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology…”

But once again, demonstrating her journalistic integrity, Fagan provides another interesting point: “Of course there’s nothing radical about presenting editing versions of ourselves, which we’ve always done…self-editing began at the beginning. The only difference now is the volume of one another’s edited lives we consume.”

Twelve days before Holleran ended her life, a friend sent her a link to an article called “Ivy League Quitters: The Cost of Being an Ivy Athlete.” Like those of us who self-edit, Holleran was not the first (and unfortunately will most likely not be the last) to feel the way she did about college sports. But it didn’t matter. Sports were always a huge part of her identity and it was a hard to let that go. There was also the mentality of perfection – and as the late preacher Maurice Boys so poignantly said: “Notice how closes perfection is to despair.” By including this quote in her book, Fagan point outs that there are a lot of fine lines being walked by people who suffer from mental illness.

As I’m writing this, it has come to my attention – via social media of course – that next week is Suicide Awareness Week. Hopefully social media platforms do actually help spread awareness about this issue. I can’t possibly imagine what it was (and continues to be) like for the people close to Holleran to find out that they were too late to help someone they didn’t know needed help.

Leave a Reply